Culture

‘When you write a travel book, you need to have terrible things happen to you’

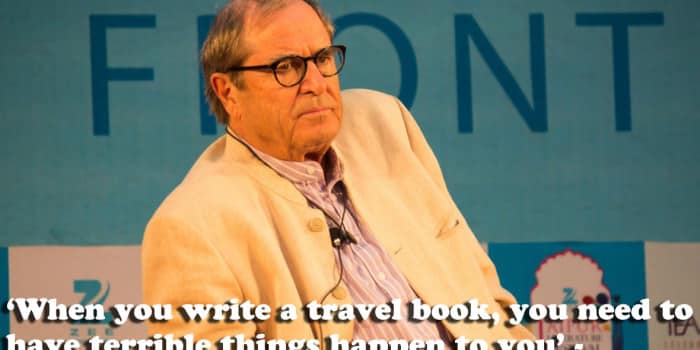

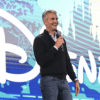

Paul Theroux at the Zee Jaipur Literature Festival 2015.

Tall and aloof, with the stern-ish look on his face punctuated by dark sunglasses, Paul Theroux’s presence at the Zee Jaipur Literature Festival was significant and noticeable. He was there as a travel writer, novelist, critic and erstwhile protégé of VS Naipaul. He was also the object of my interest, as I sought to interview him.

In his JLF session, ‘My Other Life: A Novelist’s Affair with Non-fiction,’ I sat near the front and listened with rapt attention as Theroux addressed the motivation behind his first travel book.

“Sometimes, you have to leave home to find something to write about,” Theroux said, about his decision to take a train trip across Europe and Asia, and back again in 1974. That trip famously resulted in the ground-breaking travel book, ‘The Great Railway Bazaar’, which forged a new style of travel writing, a new genre, based on first-person narrative.

It was Theroux’s first foray into travel writing, and he said he did it out of necessity. “I needed to pay the rent and I wanted something easy to do. I decided on the railway journey because no one had done it and it seemed like a simple idea. At the end, I would have a book.”

Listening to Paul Theroux in the Non-fiction session, and also the one called ‘Wanderlust and the Art of Travel Writing’, at the JLF, and talking to him on the airy press terrace overlooking the lawns, I marvelled at my luck at meeting him in India, where he has travelled extensively. I still didn’t have my interview, but I was certainly getting to know more about him, and his association with India.

In ‘The Great Railway Bazaar’, Theroux spends considerable time taking trains across India, and he describes his journeys in gritty, and affectionate, detail. On the Kalka-Simla “toy train”, he meets the Accountant General of the Punjab. On the Rajdhani from Delhi to Mumbai, he gets down at Mathura and talks to pilgrims, there on yatra. Before taking the Delhi mail from Jaipur, he allows a misinformed local to guide him around the city. On the Grand Trunk Express, he meets a series of heart-breaking beggars.

But in this book, and in others about India—such as ‘The Elephanta Suite’—Theroux doesn’t blink when writing about India. He sees India with unvarnished eyes. You won’t find any romantic gilding in his travel writing. “Travel writers have an obligation to tell the truth,” he said. “The truth is prophetic,” he said.

Painting a picture of the ideal scenario for a travel writer’s journey, Theroux said they should travel rough and not be in a hurry. “Comfort, speed and efficiency are the enemies of observation.”

Paul Theroux is very much of the “if it almost killed you, it’s a good story” school of travel writing. He said his greatest experiences were life-threatening and told some anecdotes about young men waving old guns at him in Africa and young men pointing rusty spears at him in Indonesia. “Travel hardship makes a good story,” he said. “When you write a travel book, you need to have terrible things happen to you.”

When everything’s fine, there’s nothing to write about. You need to be alone when you travel, you need to take risks, you need to be lonely. “When you’re alone and uncomfortable, things happen.”

In spite of this macho bravado, Theroux does indeed seem to have the sensitivity of a traveller’s soul. “I travel for pleasure, not to suffer, but to find something out. I travel out of curiosity and the pleasure of discovery. The difference between a traveller and a tourist is that a traveller is not in a hurry.”

He also stressed the need for anonymity. “The last thing you want is to be noticed, to be the object of curiosity. You can’t be a travel writer if you’re a celebrity. You need to be able to eavesdrop. You should cultivate your humility. Travel should teach you that you’re very small.”

While I don’t doubt the sincerity and wisdom of his words, it was Theroux’s celebrity that made it hard for me to pin him down to an interview. Yet, I kept seeing him on stage, in the audience, on the press terrace and, memorably, on the lawn at the Rambagh Palace, having lunch his wife, Sheila, son Marcel and VS Naipaul.

In the end, I felt satisfied. He was gracious with me, as well as elusive, when we interacted, and I think that’s who he is. He controls how much he reveals about himself in his writing and in his talks. He is after all the consummate travel writer, the observer who opens a window, not to himself, but to the world.