Culture

Classic periodic table design to its pop culture avatar: Non metallic evolution

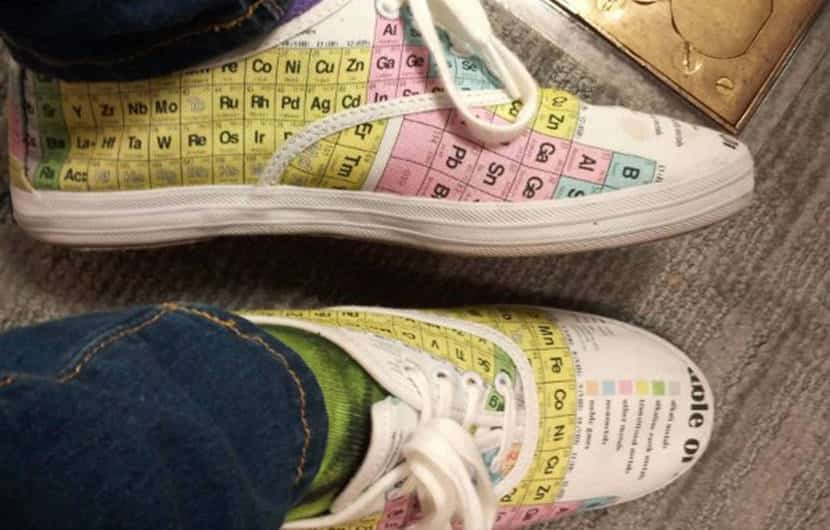

The periodic table is one of those classic images that you find in many science labs and classrooms. It’s an image almost everyone has seen at some time in their life.

You can also find the periodic table on t-shirts, mugs, beach towels, pillowcases and duvet covers, and plenty of other items. It even inspired a collection of short stories.

Who can forget the periodic table put to music by the American Tom Lehrer, a Harvard mathematics professor who was also a singer/songwriter and satirist. His song, The Elements, includes all the elements that were known at the time of writing in 1959.

Since then, several new elements have been added to the periodic table, including the four that were formally approved last year by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC).

But what exactly does the periodic table show?

In brief, it is an attempt to organise the collection of the elements – all of the known pure compounds made from a single type of atom.

There are two ways to look at how the periodic table is constructed, based on either the observed properties of the elements contained within it, or on the subatomic construction of the atoms that form each element.

The elements

When scientists began collecting elements in the 1700s and 1800s, slowly identifying new ones over decades of research, they began to notice patterns and similarities in their physical properties. Some were gases, some were shiny metals, some reacted violently with water, and so on.

At the time when elements were first being discovered, the structure of atoms was not known. Scientists began to look at ways to arrange them systematically so that similar properties could be grouped together, just as someone collecting seashells might try to organise them by shape or colour.

The task was made more difficult because not all of the elements were known. This left gaps, which made deciphering patterns a bit like trying to assemble a jigsaw puzzle with missing pieces.

Different scientists came up with different types of tables. The first version of the current table is generally attributed to Russian chemistry professor Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869, with an updated version in 1871.

Importantly, Mendeleev left gaps in the table where he thought missing elements should be placed. Over time, these gaps were filled in and the final version as we know it today emerged.

The atoms

To really understand the final structure of the periodic table, we need to understand a bit about atoms and how they are constructed. Atoms have a central core (the nucleus) made up of smaller particles called protons and neutrons.

It is the number of protons that gives an element its atomic number – the number generally found in the top left corner of each box in the periodic table.

Shutterstock/duntaro

The periodic table is arranged in order of increasing atomic number (left to right, top to bottom). It ranges from element 1 (hydrogen H) in the top left, to the newly approved element 118 (oganesson Og) in the bottom right.

The number of neutrons in the nucleus can vary. This gives rise to different isotopes for every element.

For example, you may have heard of carbon-14 dating to determine the age of objects. This isotope is a radioactive version of normal carbon C (or carbon-12) that has two extra neutrons.

But why is there a separate box of elements below the main table, and why is the main table an odd shape, with a bite taken out of the top? That comes down to how the other component of the atom – the electrons – are arranged.

The electrons

We tend to think of atoms as built a bit like onions, with seven layers of electrons called “shells”, labelled K, L, M, N, O, P, and Q, surrounding the core nucleus.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Each row in the periodic table sort of corresponds to filling up one of these shells with electrons. Each shell has subshells, and the order in which the shells/subshells get filled is based on the energy required, although it’s a complicated process. We’ll come back to these later.

In simple terms, the first element in each row starts a new shell containing one electron, while the last element in each row has two (or one for the the first row) of the subshells in the outer shell fully occupied. These differences in electrons also account for some of the similarities in properties between elements.

With the one or two subshells in the outer layer full of electrons, the last elements of each row are quite unreactive, as there are no holes or gaps in the outer shell to interact with other atoms.

This is why elements in the last column, such as helium He, neon (Ne), argon (Ar) and so on, are called the noble gases (or inert gases). They are all gases and they are “noble” because they rarely associate with other elements.

In contrast, the elements of the first column, with the exception of hydrogen (just like English grammar, there’s always an exception!), are called alkali metals. The first-column elements are metal-like in character, but with only one electron in the outer shell, they are very reactive as this lone electron is very easy to engage in chemical bonding. When added to water, they quickly react to form an alkaline (basic) solution.

Each shell can accommodate an increasing number of electrons. The first shell (K) only fits two, so the first row of the periodic table has only two elements: hydrogen (H) with one electron, and helium (He) with two.

The second shell (L) fits eight electrons. Thus the second row of the periodic table contains eight elements, with a gap left between hydrogen and helium to accommodate the extra six.

The third shell (M) fits 18 electrons, but the third row still only has eight elements. This is because the extra ten electrons don’t get added to this layer until after the first two electrons are added to the fourth shell (N) (we’ll get to why, later).

So the gap is expanded in the fourth row to accommodate the additional ten elements, leading to the “bite” out of the top of the table. The extra ten compounds in the middle section are called the transition metals.

The fourth shell holds 32 electrons, but again the extra electrons are not added to this shell until some have also been added to the fifth (O) and sixth (P) shells, meaning that both the fourth and fifth rows hold 18 elements.

For the next two rows (sixth and seventh), rather than further expanding the table sideways to include these extra 14 elements, which would make it too wide to easily read, they have been inserted as a block of two rows, called the lanthanoids (elements 57 to 71) and actinoids (elements 89 to 103), below the main table.

You can see where they would fit in if the periodic table was widened, if you look at the bottom two squares in the third column of the table above.

Across the columns

There is another complicating factor leading to the final shape of the table. As mentioned earlier, as the electrons are added to each layer they go into different subshells (or orbitals), which describes locations around the nucleus where they are most likely to be found. These are known by the letters s, p, d and f.

The letters used for the orbitals are actually derived from descriptions of the emission or absorption of light due to electrons moving between the orbitals: sharp, principal, diffuse and fundamental.

Each shell has its own configuration of subshells named from 1s through to 7p, which gives the total number of electrons in each shell as we progress through the periodic table.

As mentioned earlier the order in which the subshells fill with electrons is not so straightforward. You can see the order in which they fill from the image below, just follow the order as you would read down from left to right.

There is an interactive periodic table that also illustrates the filling sequence well if you click through the atoms.

Elements within a column generally have similar properties, but in some places elements side by side can also be similar. For example, in the transition metals the cluster of precious metals around copper (Cu), silver (Ag), gold (Au), palladium (Pd) and platinum (Pt) are quite alike.

Most of the existing elements with high atomic numbers, including the four superheavy elements added last year, are very unstable and have never been detected in, or isolated from, nature.

Instead, they are created and analysed in minute quantities under highly artificial conditions. Theoretically, there could be further elements beyond the 118 now known (there are additional g, h and i suborbitals), but we don’t know yet if any of these would be stable enough to be isolated.

A classic design

The periodic table has seen many colourful and informative versions created over the years.

One of my favourites is an artistic version with original artworks for each element commissioned by the Royal Australian Chemical Institute to celebrate the International Year of Chemistry in 2011.

Another favourite is an interactive version with pictures of the elements. The creators of this site have also published a coffee table book called The Elements and an Apple app with videos of each element.

Interactive versions have also been created by the Royal Society of Chemistry (and can also be downloaded as an app) and ChemEd DL among others.

The classic design of the periodic table can be used to play a version of the Battleship game.

There are also many fun versions created to help organise a multitude of objects, including food, beer, emojis, iPad apps and birds.

As for Tom Lehrer’s The Elements, the song has yet to be updated to include all the elements known today but it has been covered by other people over the years.

Actor Daniel Radcliffe, of Harry Potter fame, performed a version during a guest appearance on the BBC’s Graham Norton Show.

There are other musical versions of the elements but they too have yet to be updated to include all entries of the periodic table.

In summary, the periodic table is the chemist’s taxonomy of all elements. Its triumph is that it is still highly relevant to scientists, while also becoming embedded in popular culture.

Mark Blaskovich, Senior Research Officer, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publication