Opinion

Silence over the Release of Bilkis Bano’s rapists – Deteriorating India’s Collective Conscience?

In the winter of 2012, the nationwide protests for action against Nirbhaya’s rape accused spread all over the country. Young men and women got out of their homes, assembled with their friends and thronged the wide pavements of Rajpath to shout, albeit angry but revolutionary, slogans of justice. Their only demand was that the men charged with the horrific sexual assault and murder of the 23-year-old physiotherapy student should see the harshest of punishment – even if it meant a change in legislation.

Even though it was a moment of tragedy, it also gave many Indians a sense of hope. We thought: “probably, this will reverse the trend of regular violence against women. Maybe, they will be able to get out of their homes without fear.” It was time for churning. Finally, the nation’s collective conscience had awakened, we thought.

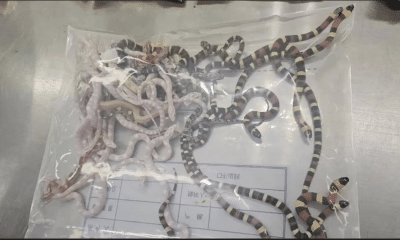

Ten years later, the photos of convicted rapists of Bilkis Bano being felicitated and garlanded are all over social media. Whether they are real or not is not known, but the release of these men itself opens a pandora’s box for the future of women’s safety in India.

The eleven men convicted and sentenced by the High court were released after the Gujarat government set up a panel for the remission of their sentence. On September 10, India’s Supreme Court took notice of petitions challenging the remission of these convicts and asked the Gujarat government to place before it all relevant records in the case within three weeks. It was a sign that the release of the eleven men didn’t go down well with India’s top court.

Ironically enough, the convicted men were released on August 15, the day when India was celebrating 75 years of its independence and the day Prime Minister Narendra Modi exhorted his countrymen from the historic Red Fort to respect its women.

On that auspicious day, for some reason, the Gujarat government thought the freedom that our forefathers fought for together should somehow be extended to the men who not only gang raped Bano but also participated in a massacre of her family.

It happened twenty years ago, on February 28, 2002. After the riots broke out across Gujarat, the family of Bilkis Bano tried to flee their town in a truck. On the way, they were intercepted by a mob just outside the borders of Ahmedabad. As she witnessed the dance of death, 14 members of her family were killed in front of her eyes.

I always imagined how helpless she would have felt at that moment in time, probably suspended in her memory for the rest of her life. How her heart would have shattered when the rioters decided to smash the head of Saleha, her three-year-old daughter, on the ground, instantly killing her? How numb she would be when she, pregnant with another child, was gang-aped and brutalized by men burning in wrath and hatred of the other? The only reason she was left behind was that the mob mistook her to be dead.

All the men who committed this horrendous act were known to Bilkis Bano and her family. A few were neighbours or who lived in the same locality, and others did business with them.

In 2004, these men were arrested amid Bano’s apprehensions and fears that witnesses in the case were being intimidated by powerful people and evidence was being tampered with. Because of that, the case was transferred to Mumbai. In 2008, these eleven men were convicted of their crimes by a special CBI Court, a sentence upheld by the High Court in 2017. In the years following her ordeal, most of the men charged for leading the riots were let go for want of evidence. The eleven men were among the handful of rioters who were eventually convicted because of the pressure created by civil society and the national media.

At that time, the collective conscience of India wanted those accountable for the pain suffered by Bilkis to be brought to justice. Since then, our nation’s collective conscience has numbed down, and with that, our sense of morality and justice as a country.

This new collective conscience of the present times doesn’t value the life and dignity of other communities and is a victim to majority appeasement. When the state and courts are creating harsher laws against sexual assault, a state government can bat for a reduction in the sentence of convicted rapists, which is a testament to this numbness of our hearts.

This decline in the sensitivity of our conscience might have sprouted when a few men in Dadri, convicted of lynching to death Mohammed Akhlaq in 2015 on ‘suspicion’ of slaughtering a cow, were garlanded by none other than a national politician. It would have evolved into its ugly avatar when the killers of Pehlu Khan, caught on video beating him to death, were released by courts for ‘lack of evidence’. Or when cops beat up injured Muslim men during the 2020 Delhi riots, exhorting them to sing the national anthem – one of those later dying mysteriously in police custody. Our sense of justice was further tested when we didn’t say enough about a 22-year-old ‘love jihad’ accused who, police said, committed suicide by hanging himself on a tap – at a time when all CCTV cameras in the police station had mysteriously stopped working.

The silence that reigns in the current dispensation on this targeted neglect of one community isn’t bound by just the class. It extends to celebrities too. When in 2021, Indian cricketer Mohammed Shami faced hate speech on social media for his performance in an India-Pakistan match, none from the government or BCCI stood up for him. His captain Virat Kohli eventually spoke for him and soon became fodder for trolls. When on August 12, Indian-origin Booker Prize writer Salman Rushdie was stabbed at a New York lecture, many expected immediate state condemnation from India’s Ministry of External Affairs. However, it took nearly two weeks for the Indian government to even acknowledge it. Mostly social media-savvy Prime Minister Modi never issued an official statement.

It seems the silence of attacks on Muslims is expanding, and that includes the media. After the release of the eleven convicts in the Bilkis Bano case, a news investigation found that none of them was living in their homes, even as the Supreme Court heard a petition moved by Subhashini Ali, Revathi Laul and Prof. Roop Rekha Verma, challenging the remission. Some of their family members said they were on pilgrimage, and others said they had no idea of their whereabouts. I ask if they commit another such crime, will the Gujarat government take responsibility for it?

It’s also a sign that we had forgotten the lessons we learned from Nirbhaya’s ordeal when Indians – regardless of their religion – came out to demand harsher punishment for sexual assault. It’s time India steps in to punish the perpetrators of crimes against any woman, whatever their religion might be. If we fail to do so, it sets a precedent that someone else can do the same with impunity and eventually get away with it: that is, women and men of one community are fair game for violence in today’s India.

While in cases like that of Nirbhaya and the infamous 2019 Hyderabad rape case, there was huge attention by television media and, thus, pressure on law enforcement to act, few television debates talked about the injustice meted out to Bilkis. There is an utter silence on the lips of those who once shouted from the mics and podiums. It might be that their hearts are guilty, just like all of us who stand helpless and without a voice. If courts don’t act to reverse the decision, this spiral of silence will grow and weaken the collective conscience of India until there is nothing left for anyone to fight for.

After the remission, Bilkis told the media her faith in justice was shaken. She said: “When I heard that the convicts who had devastated my family and life had walked free, I was bereft of words. I am still numb.” You are not the only one who is numb, Bilkis. All of us are, whether we know it or not.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the publication